Looking back to the spring of 2024 and my Innovation and Design Thinking course with Professor Emily Harris, it’s amazing to think that what began as a small class project has grown into such a significant part of my time at Notre Dame. For our project, Adam Herrera ('26), Alex Mazzucco ('26), Rocco Pacchiana ('26) and I created a board game for the students of Saint Bakhita Vocational Training Center as part of a broader prompt to support the students’ thriving after their graduation. The board game, titled “Bakhita Business”, aims to foster family dialogue around the value of reinvesting in a business by illustrating the journey of a young tailoring entrepreneur. It presents players with a series of complex choices related to business and financial management, mirroring the difficult reality of the pressured decisions the scholars are forced to make between long-term investment or the immediate needs of themselves, their businesses and their families.

During the semester, we were able to do limited prototyping with the students and staff of SBVTC via Zoom calls and emails; enough to validate the idea, but not enough to work through many of the complexities. There was enough momentum and excitement for the idea, however, that work on the game continued beyond the semester and made its way onto the list of priority projects for the Winter 2025 immersion, and I’m so grateful to my classmate, Jessica Vickery (’25), for all of her experience and insights during that trip which helped develop the board game through in-person testing with stakeholders, feedback generation and collection, and prototype revision! Her work resulted in a few key improvements in the game, including clearer instructions, translation of the materials into Acholi, a more accessible color palette, and richer storytelling on the choice cards.

Then came the opportunity for me to join the spring break immersion trip to Uganda this spring, and I was thrilled, both for the opportunity to reconnect with the SBVTC community as well as the chance to finally play the board game in person with the students! I went into the trip with three main goals:

Observe the actual gameplay experience

Study whether the game is shifting mindsets

Evaluate whether the game is still solving the right problem.

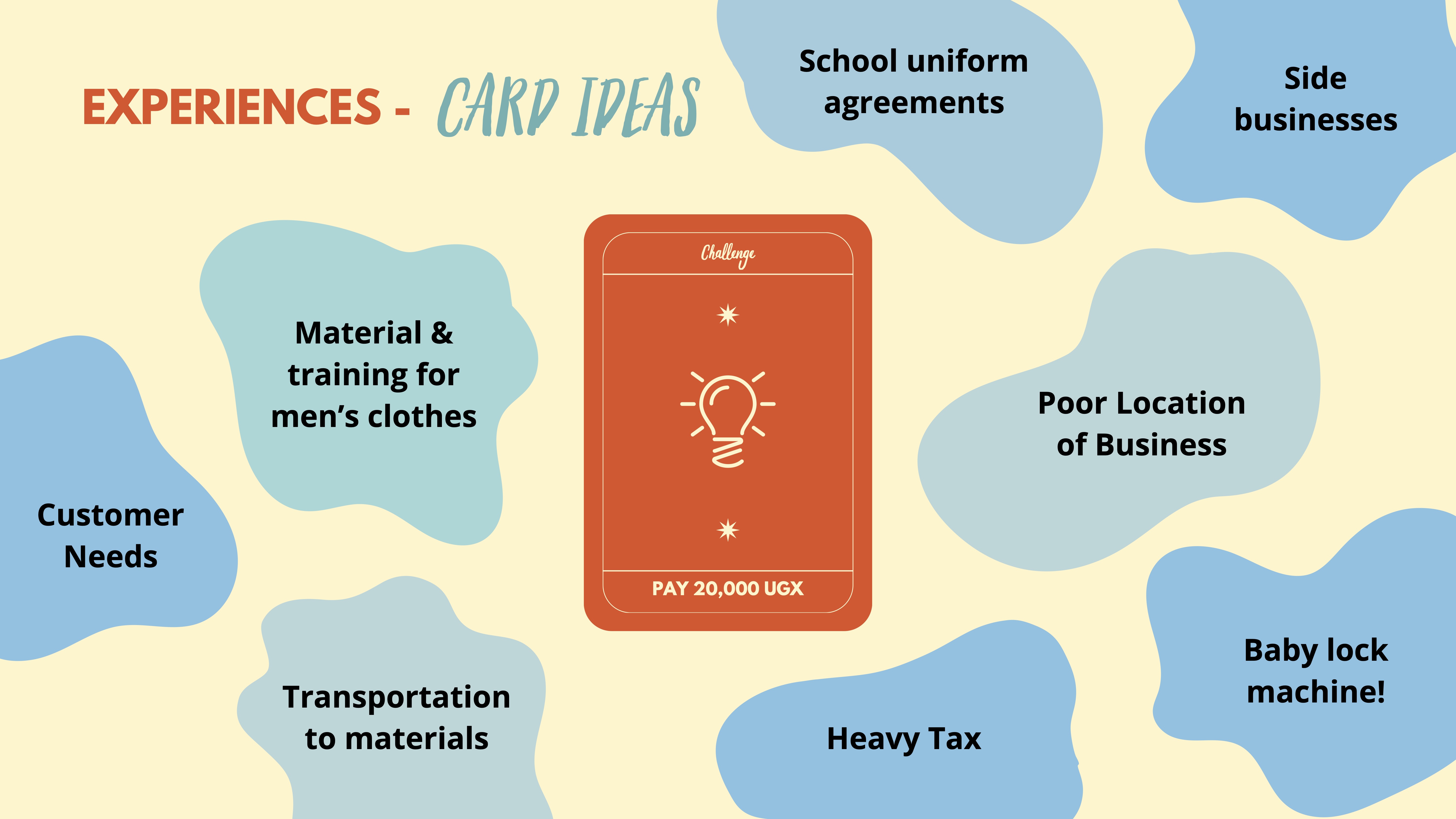

To pursue these goals, I conducted multiple testing sessions using two methods: letting groups play while observing and collecting pre- and post-surveys; and facilitating co-creation workshops where participants helped generate card ideas, offer critiques and shape the game themselves. I enlisted current Innovation Scholars, recent alumni, and several staff members from SBVTC to play the game and provide feedback. I quickly learned many detailed adjustments to the game play, but also appreciated so much those whose willingness to share stories will continue to better shape the game to more accurately reflect the lived experience of tailoring entrepreneurs.

As I hoped, getting to play the game that I helped create with the audience it was intended for was deeply rewarding and so energizing! And it helped complete my first goal of observing gameplay. Observation brought four main learnings:

The actual gameplay experience was good (I was a little nervous about this)! Most scholars had never played a board game before, but they caught on quickly. They enjoyed it and grasped key concepts through play. This confirmed that the game’s complexity was well-suited for new learners—but also revealed that adding more layers might not be helpful going forward.

The game works. Players who made smart reinvestment choices consistently won. However, because many scholars were unfamiliar with strategic gameplay, some of the deeper lessons weren’t always intuitive. If the lesson of reinvestment comes from discovering how to win, but players aren’t actively seeking a winning strategy, that lesson might not stick without guidance.

Language complexity remains a challenge, even with Acholi translations. This means that the game is likely best used in a facilitated educational setting. While the original idea was that scholars could take it home to play with their families, it seems clear that its value is maximized when the game is introduced with intentional teaching. It works, but it needs support.

And perhaps most importantly: the game was fun! Scholars were engaged, laughing, and connecting. And for me, it was incredibly meaningful to see something that started in a classroom come to life on the grounds of Saint Bakhita one year later.

The second goal of evaluating how the game might shift mindsets was a little tougher to clarify and I think deserves longer-term research. In our limited time, scholars often relied on facilitators and didn’t always engage deeply with the game’s decision-making strategy. Still, the core message resonated. One scholar reflected: “I always hurry to support my family not knowing that I will go backward in my business.”

Such comments suggest that the lesson was understood in the moment, but whether it affects long-term behavior remains an open question and will be a priority for future exploration.

Lastly, and most critically, was the goal of determining if we’re still solving the right problem. As with any design thinking project which places customer needs first, we are constantly asking ourselves if we’re still on the right track and addressing real needs. We created this game with the hope of empowering alumni to have complex conversations with their family, in a way that respects both tradition and growth. Thankfully, I think we’re still doing that.

Throughout the games, parental pressure emerged as a central – but nuanced – barrier to reinvestment. Some parents see business profits as short-term returns on their investment in their daughters’ education. One staff member described one such complexity, noting that “some parents think if they paid for school, the business profits are a return to them.” Yet not all scholars face this pressure; family expectations vary widely, as some families don’t have any expectations for their daughters to share business profits or resources. Interestingly, it sounds like recent contracts used in the new incubator program for SBVTC alumni might be creating clearer alignment between parents and their students. That raised an important question for me with respect to the game: is the Bakhita Business the best tool to solve this problem, or are there other mechanisms – like the contract – which might be more effective?

Going forward, I think the next steps are:

Continue researching how the game affects the long-term decision-making of SBVTC alumni

Explore how the game might complement other tools to help align the values and aspirations of the scholars and their families even more closely

Refine the game’s components and develop a sustainable distribution strategy in alignment with the broader goals of SBVTC and the Powerful Means Initiative.

On a personal note, it’s hard to put into words how special it was to see an idea that started in a classroom become a board game I got to play with students in Uganda. Seeing a project come to life like that is something I’ll never forget. I’m forever changed by the way this work has taught me to learn and walk alongside others. I’m still processing the difficult realities we encountered in creating and testing this game, but I’m also filled with hope. I’m excited to continue supporting this project as an ND alumnus, and I can’t wait to see the final version in the hands of the girls themselves.

This project raised as many questions as it answered—but that’s part of the process. And from my perspective, the board game remains a promising educational tool, a bridge for family dialogue and potentially even a scalable product. Whether through gameplay, storytelling, or strategic thinking, Bakhita Business is helping young women think long-term—and that’s a win worth investing in.

Mya McClure is a graduate (class of 2025) of Notre Dame's Mendoza College of Business, where she majored in Management Consulting and Sociology.